You’ll need to finish the lesson first! When you’ve read through each chapter, and found the 12 ways we can improve Orang Asli access to education, you’ll unlock this reward which you can share with your friends!

You've found 1 solution(s)! 11 more to go! Keep track of your progress with this scorecard here.

Find all the solutions to unlock your reward

Read the 12 recommended solutions in this research paper.

YOUR SCORECARD:

Recommendation 1: There must be a greater focus on learning and addressing underlying challenges instead of symptomatic issues.

The general school culture must prioritise learning instead of examinations or rote memorisation. High-quality education that can motivate and nurture students is needed to produce Orang Asli students who are independent learners. Policies and programmes need to address underlying issues instead of only dealing with symptomatic problems at a surface level which do not resolve or eradicate these issues.

Recommendation 2: Indigenous cultures and history must be integrated into the mainstream curriculum.

It is very important that indigenous cultures and history be included in the mainstream curriculum, and that Orang Asli should not be represented as an exotic “other”, but celebrated as part of the diversity of peoples in Malaysia. Schoolchildren should be taught about different Orang Asli sub-ethnic groups, where they live, their contribution to nation-making, their arts, and their cultures that are closely linked to the natural environment.

The Orang Asli's rights to self-determination as indigenous peoples should also be included in mainstream education.

Recommendation 3: Existing programmes must be monitored and evaluated to ensure their efficient and effective delivery and implementation.

Regular monitoring, and mid- and post-programme evaluations are needed to ensure that programmes remain on track and are adjusted for new issues that may arise. This monitoring and evaluation needs to be considered at the beginning of the original programme design.

Recommendation 4: Teachers and school leaders who are equipped and capable of delivering quality education for Orang Asli students need to be entrusted with greater autonomy and balanced accountability.

Teachers and school leaders who are able to enhance the quality of education for Orang Asli students should be given the freedom to do so, as they could be role models that drive change. However, this autonomy needs to be balanced with accountability. These teachers and school leaders also need to be further trained and equipped to fully leverage this autonomy to deliver effective teaching and learning along with the efficient allocation of resources.

Recommendation 5: Pre-posting training on Orang Asli cultures could be provided to teachers, and infrastructure and resources for teachers in Orang Asli schools should be improved.

Teachers who are posted to schools with Orang Asli students should be provided with training to introduce them to the history and culture of the particular Orang Asli sub-ethnic group they will be teaching. This preparation module could also include implicit bias training to create self- awareness of learned racial biases against Orang Asli.

Teachers who are posted in Orang Asli schools often take up many different responsibilities outside the classroom, such as taking care of students after school and maintaining the school’s infrastructure. These teachers should be given more support and increased allowances for these added responsibilities. Their living conditions and teaching infrastructure could also be improved.

Recommendation 6: Teachers should be trained in innovative and adaptive pedagogies, and platforms for knowledge sharing could be established.

Teachers should be introduced to different teaching tools such as culturally responsive and adaptive pedagogies, both before and during their postings, with experienced teachers encouraged to share their best practices and offer advice to new teachers.

Other knowledge sharing initiatives could include annual teaching conferences, to foster networking and support among teachers; and user-friendly online knowledge sharing platforms as a resource for teachers.

Teachers often use their private funds to create innovative teaching tools. They should be supported, and a teaching and learning fund be made available to teachers. Recognition should also be given to teachers and schools for their best practices.

Recommendation 7: Trust and collaboration between schools and Orang Asli communities needs to be built as Orang Asli parents and their communities are important partners in education.

This is critical in creating a supportive environment for Orang Asli children. Schools and communities should have open communication and work collaboratively. Schools can also draw upon the community’s expertise and local knowledge as part of the learning experience for their students.

Recommendation 8: Community-based schools (PDK) need to be recognised as part of the support system for schools and adequate essential resources should be provided to PDKs.

Support and recognition should be given to PDKs for their important role in community education. PDKs provide preschool education, after-school programmes and in some cases alternative schooling for children without access to public schools or those who have dropped out. Some PDKs also provide learning opportunities for adults in the community.

Support can be in the form of funding and resource assistance to PDKs, including infrastructure such as libraries, computers and reliable internet connection. However, their autonomy should remain an important feature of their governance structure.

Recommendation 9: Good quality preschool education needs to be provided based on learning through play, social interaction, and their environment.

Orang Asli students without access to preschools are at a disadvantage when they enter Standard 1, as the curriculum assumes that students can already read, write, and count. Teachers have to pay special attention to teach them these basic skills, but this may not be possible given large class sizes. Students who attend preschool may also be more confident in their abilities and are able to transition to schooling life better. There are many villages without access to preschools and the founding of more community-based learning centres (PDK) could play an important role in providing preschool education for Orang Asli children.

Recommendation 10: Orang Asli communities should be empowered to be their own agents of change and participate in the process of Orang Asli-related policies.

This ensures that their cultures and views are incorporated in policymaking. Education issues and challenges should be addressed with Orang Asli parents and communities at the school, state, and national levels.

The creation of an Orang Asli education council comprising Orang Asli leaders, education policymakers, principals, teachers, and other relevant stakeholders to govern and monitor the progress of policy and programmes for children would help to ensure voices of the Orang Asli are fully taken into account and are involved in the close monitoring of any programmes.

Recommendation 11: Create a strength-based discourse to shift away from the current deficit discourse on Orang Asli.

Orang Asli students’ high dropout rate and gap in educational achievement are often attributed to their culture and way of life. All stakeholders need to move away from this 'deficit discourse', and instead adopt a strength-based framing that values Orang Asli culture as an asset. This includes shifting to culturally responsive teaching methods that draw on the students' cultural context to make learning relevant and effective.

Recommendation 12: The collaboration of relevant ministries must be strengthened to address the multidimensional challenges that Orang Asli children and communities face.

Multiple agencies need to coordinate in order to provide access to high-quality education. This includes building schools that are close to the villages, providing safe and reliable transportation and roads, and financial and resource assistance to families and schools.

Infrastructure such as hostels, libraries, computer centres, and internet connectivity are also desperately needed.

At the village level, basic amenities like electricity and clean water are vital.

The cooperation of NGOs and other charitable foundations are also needed in this effort. Information flow and transparency on the availability of assistance also need to be addressed so that parents and students are aware of and have access to the assistance and resources available to them.

Selah’s favourite memory is of eating snow in Turkey. She doesn’t say it’s her favourite – in fact she tries not to show her pride – but she starts offering details unbidden, forming a story rather than merely answering our questions.

She was 10 years old then, on her first trip abroad, as part of a team representing Malaysia at an international dance competition. While in Turkey, they spent a day visiting a snow-capped mountain.

You can eat snow? we ask. “Yes, you can,” she replies, beginning to laugh at the recollection. “You see, the snow is thick so you take it from underneath. It’s not dirty at all, if you take the clean bits.”

They went to Cappadocia too, she tells, but downplays her story by saying they were late and missed the popular tourist spectacle of hot air balloons rising en masse in the mornings.

So luminant were those memories, that the dance competition itself faded in significance. “We didn’t win, we were tenth or ninth,” she says when we ask about the results. “I felt like, it’s ok that we didn’t win.” She lets out a conspiratorial laugh. “After all, they won in their own country! I don’t know why, but Turkey won, they were first.”

A lull in the conversation brings back the forest sounds of this shallow valley in Gombak, on the edges of Kuala Lumpur’s urban sprawl. The blanket sound of shrill insects, punctured by occasional bird calls, with the low drone of the highway traffic in the distance.

This is the landscape Selah and her family calls home. They are Orang Asli, of the Semai people, although they reside in a traditionally Temuan area. Selah and the children from her village attend the government school nearby, where they are a minority in the student body, alongside majority Malay classmates. This is often the case for Orang Asli communities, like Selah’s, who live near or within mainstream populations.

“If it were up to me, I would make a school where the rules aren’t so tight,” says Selah, when we ask her to describe the school of her dreams. “So it doesn’t feel so forced, in a more relaxed way.”

“And for me, I would like to learn dance. Other subjects like maths, science – we can have them, but less.”

“I don’t know why, but I just like dancing, since Standard Four when I joined the dance team.”

That’s when the conversation turned to dance, Turkey and snow.

“At the time (of the competition), it was a mix,” she says of their performance in Turkey. “We had Malay traditional dance, Chinese, Indian...” her voice trails off a bit. “It was Malaysian lah,” she finally says.

Was Semai dance included? we ask. “No, there were no Orang Asli dances (in the performance).”

Could it have been part of the performance? “Yes,” she says slowly, as if exploring the idea for the first time in her head. “If they want it in the performance, then yes it’s possible. But if they don’t want it, what can I do?”

Did you try suggesting this to the teacher? “No,” she pauses. “I just went along with things.”

Including Selah, there were six Orang Asli dancers in the team, out of 23.

According to IDEAS’ research, there is a lack of participation among Orang Asli students and parents in education, often stemming from a sense of disconnect with schools.

“Orang Asli students might attend school, but they often feel like they don’t belong, like schools are something external and not something over which they have any control,” says Universiti Malaya senior lecturer Dr Rusaslina Idrus, who co-authored the paper.

“Imagine going to school, where it is common to see murals that celebrate diversity by showing only the three mainstream races. Now, they might not articulate it immediately, but the message that Orang Asli don’t belong is being internalised, in both Orang Asli and non-Orang Asli children.”

Moreover, Orang Asli children find themselves studying a syllabus that is meant for mainstream populations – a syllabus filled with concepts that are immediately familiar to most children, but many that are alien to the Orang Asli. This exacerbates the disconnect they feel in school.

It is little wonder that IDEAS’ research showed bullying and discrimination as two of the most common issues raised by Orang Asli who attend government schools.

One Orang Asli student interviewed by IDEAS remembers being called “pendatang”, or “foreigner”, by her classmates. The irony was not lost on her.

Other students report hearing Orang Asli described as “dirty“ or “stupid”.

“No one is born racist. These are learned behaviours, fostered in an environment that is ripe for discriminatory notions against Orang Asli to grow,” says Dr Rusaslina. “When you look through the textbooks today, there is precious little about Orang Asli culture or history, so how would our children know about them?”

Although Selah’s school is barely five minutes’ drive away – along a two-way trunk road dotted with Malay food stalls, houses, and Orang Asli settlements – the forest where we are speaking to her seems a world away.

Here, they belong.

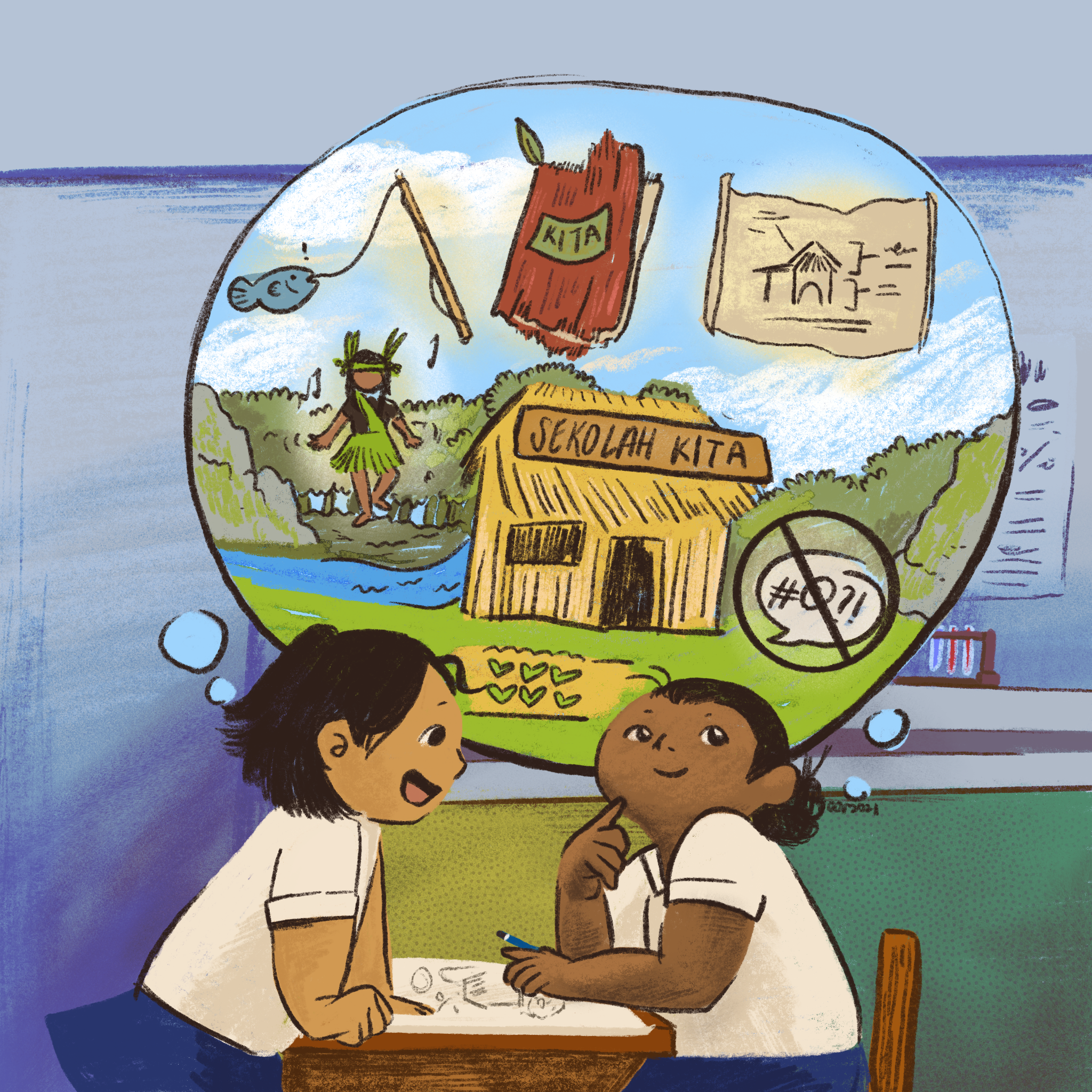

“I want a school that’s in the forest, just a simple building,” says Sonia, Selah’s elder sister, whom we are interviewing together with Selah. “Because here it’s quiet and cool.”

“We’d use books of paper made from the trees, like recycled,” she continues. “We would learn how to catch fish, build houses, about how animals live.”

How to survive in the forest, how to start a fire, how to find vegetables – all part of Sonia’s dream school syllabus, a syllabus most urban children would fail at.

And how would the school environment be? Both Selah and Sonia had the same answer.

“The environment would be like, we can all be friends,” says Sonia. “There is no envy or jealousy among us.”

Selah chimes in: “And teachers and students, they don’t care who we are, they teach us the same, and we can be friends with everyone.”

*Names of children changed to protect their identities. This interview with Selah and Sonia was conducted independent of IDEAS’ research interviews.

You have completed this chapter

You have completed this chapter